Multimedia artist Nida Bangash is featured at Clay and Canvas Studio’s Open Studio Night

Since December of 2011, artists and educators Lily Kuonen and Tiffany Leach have been presenting their Open Studio Night at their Clay and Canvas Studio located in Riverside. The events are held bi-annually, usually in December and May or November and April, and are a chance for art lovers to visit Kuonen and Leach’s working studio and check out the respective artists’ new work. Yet the pair also uses these events to showcase the work of both emerging and well-known artists. In the past two years, the artists Mark Creegan, Erica Adams, Jessie Gilmartin, and Rachel Evans have all been invited to present original work. While the pieces featured are highly contemporary, these one-night events have been consistently casual and benefit from Leach and Kuonen’s generosity in attempting to bring greater exposure to other artists.

This season’s event is no exception with the presentation of works by Nida Bangash. Born in 1984 in Mashhad, Iran, Bangash earned her BFA in 2006 from the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, Pakistan; two years later she received her MA in Visual Arts (with Honors) from that same school. In 2010, Bangash received a NCA/Charles Wallace Arts Fellowship, which allowed her the opportunity to study at the The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London, England. In the past six years, Bangash has worked as an educator, hosted Miniature Painting workshops at Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, been featured in over two dozen solo and group and exhibits, and won awards for her interdisciplinary vision and multi-media works. Bangash’s artist statement offers the following: “Trained in the traditions of Persian and South Asian miniatures, she employs these techniques through contemporary art that explores themes of abstraction through deconstruction or reconstruction, to cross-cultural experiences of the political, cultural and social.”

The Clay and Canvas Studio Open Studio Night featuring the work of Bangash, Leach, and Kuonen is held from 6-9 p.m. on Friday, Dec. 13 at 2642-6 Rosselle Street, in Riverside. “Turn in for parking by the minivan decked with lights,” explains Kuonen of the studio’s funky signpost/beacon. The event also features DJ e. lee from WJCT’s Indie Endeavor along with homemade treats and refreshments. The ever-magnanimous Kuonen also offers that Studio Prometheus (glass artist Kirin Hale’s studio) will also be open for the evening, and is located in the same warehouse complex as Clay and Canvas Studio. After the reception, visits to the studio are by appointment only and can be made by contacting either Tiffany Leach (at tiffanyleach.com) or Lily Kuonen (at lilykuonen.com).

I interviewed Kuonen and Bangash via e-mail; below are the transcriptions of the Q&As.

Lily Kuonen

Starehouse: How and when did you first discover Nida Bangash’s work?

Lily Kuonen: Actually, Nida found me. She recently moved to Jacksonville, and found me through the Jacksonville University website, and contacted me (I am an Assistant Professor of Art at JU). So, as a result I looked into her work to find out more about her. Once I saw her work, I was very excited to meet her.

S: What do you find so compelling about what Bangash does? In an e-mail to me, you had described her as a “miniaturist, bookmaker, and video artist.” These seem like three distinctly different mediums to work with. Along with her actual work, was it this kind of open-endedness that drew you to her?

L.K.: I think the unifying connection between the different amalgamations of her work is the narrative component of each. And the success lies in the transcendence of this narrative beyond that of language or cultural barriers. Nida was born in Iran and raised in Pakistan, and creates works using Persian traditions, yet, we can view her work her in Jacksonville, Florida and still draw a compelling narrative structure from her patterns, images, text, and video.

S: At each Clay and Canvas Open Studio event, the guest artists have been really diverse in every regard and I think the addition of Nida Bangash seems to reinforce this pattern. For example, in the past you have invited Mark Creegan, who works primarily in installation or material-based ideas that are highly conceptual and seem to almost celebrate the idea of temporality, environment, and even disposal-of-“the-work” altogether. Your last guest artist, Rachel Evans, deals more in mixed media works including figurative paintings and ceramic pieces that seem to be more overtly narrative-based. Using Creegan, Evans, and now Bangash as a kind of gauge of the diversity of artists you have presented so far, I am wondering what elements or ideas you and Tiffany are looking for when selecting a guest artist?

L.K.: You are correct in noting the differences in each artist, but what Tiffany and I look for isn’t necessarily diversity (yet that definitely makes things more interesting), instead we think about our space, and how it serves as a backdrop for the artists. This is after all an Open Studio which means we are opening up our work spaces in hospitality and community engagement. So we look for artists that will compliment or add to this type of venue. For Mark, his temporal works engaged the actual dimensions of the space. Rachel’s work was in direct dialogue with what we have named our space, Clay and Canvas Studio, since she works with both clay and paint. Nida’s work is complimentary to the intimacy of our space. Her works invite a close introspective viewing that finds a home in our modest “gallery” space.

S: How many total pieces of Bangash’s work are being featured? How many pieces are you and Tiffany each displaying?

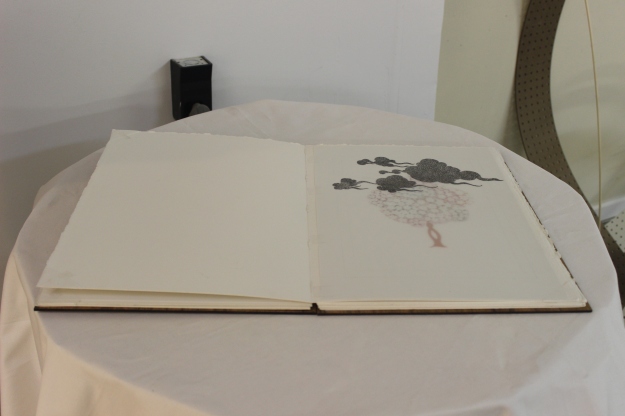

L.K.: Nida will be showing a larger painting, a grouping of nine small works on paper, a longer story/image work that unfolds on the wall, a video, and a book that is in progress. Tiffany is showing many ceramic works (both functional and sculptural). I’m not sure on the numbers, but it is a wonderful selection. I always work right up to the last minute, so I am not positive, but right now I plan to have one large drawing in progress, a couple of smaller drawings, and 5-6 PLAYNTINGS.

Nida Bangash

![[A detail shot from Nida Bangash's series "War Mannequins," water colour and graphite on waslee paper; 20cm x 20cm; 2013.]](https://starehouse.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/08-nida-bangash-war-mannequin-08-water-colour-and-graphite-on-waslee-paper-20cmx20cm-2013-5.jpg?w=960)

[A detail shot from Nida Bangash’s series “War Mannequins,” water colour and graphite on waslee paper; 20cm x 20cm; 2013.]

Nida Bangash: Roughly six to eight months. My husband is a telecom engineer and works for Nokia, he was transferred to the United States about a year ago. Hence, we are here and move from state to state every few months. Jacksonville is one of our stops.

S.: While you are showing your work in conjunction with Lily Kuonen and Tiffany Leach, I am wondering if you are personally presenting any type of set theme or cohesive idea with your pieces – or are they more of a general overview and selection or sampling of different approaches and media that you use.

N.B.: In this show, I am presenting works from War Rugs with Love series. A selection of paintings, text pieces, drawings and a video constitutes my bit in the show. My work has always been interdisciplinary. There is an underlined “theme” to the show but the approaches are different and that’s how I make work.

S.: Your website explains that you are influenced by traditional Persian and South Asian miniature paintings and that you utilize these methods in contemporary art. Did the works from these eras influence your earliest attempts at art or was it something that you learned to appreciate in hindsight?

N.B.: I have been trained as a miniature painter in my undergrad from National College of Arts, Lahore. Miniature painting is essentially a traditional art form; to learn it one needs to travel back to its roots and that’s when you find yourself looking back into your history in paintings, literature, poetry and so forth. Since I was born in Iran to an Iranian mother and raised in Pakistan where my father is from I have a lot to dig into on my plate. For me, miniature painting is like binding medium, a space where I can make sense of these two very different cultures.

Of course once the technique is learnt and the aesthetic is understood one is no longer strictly confined to the discipline, that’s the departure and that is when it comes to you more naturally and effortlessly while working as a visual artist in a broader spectrum of contemporary art.

S: Your site also mentions your interest in miniature painting created during the Mughal Empire (16th-19th c.), which seemed to evolve over time through a blending of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Muslim, and Sikhism belief systems. In those miniatures from that era, there seems to be a corollary both in visual and spiritual content with the Illuminated manuscripts that were being created in Europe in a parallel development with their Persian and South Asian counterparts. I am curious if your fascination with these miniature paintings is as much spiritual as it is aesthetically-driven?

N.B.: Certainly there is a deeper involvement; the connection is not simply aesthetic or visual-driven. The technique and involvement with the process of making itself is very contemplative and meditative. The ongoing relation between Eastern and Western art extracts from spirituality and spirituality itself derives from this connection at the very human level in the form of Global art.

S: Your site states the following: “Pattern sits at the centre of Bangash’s art practice. Her works use the language of patterns as a means of weaving together the complexities of her cross-cultural experiences.” Why is pattern so important to your work? Like focusing on the use of miniatures – which seems like a very finite or defined medium, do you find a kind of comfort or sense of direction contained within the (for lack of a better word) rigidity of pattern?

N.B.: I don’t find anything confining in giving attention to detail and I certainly don’t think there is anything confining about the use of pattern and/or geometry. They can stretch as far as your imagination can take them. For instance, look at M.C. Escher and Mondrian on one hand and Australian Aboriginal Artists on the other; the sky is the limit for what they have done with these two words which many find confining. Interesting how we find both ends these days in Modern Art Museums, no? And I believe this is the very reason pattern and the use of geometry intrigues me and I continue exploring them in my practice.

Broadly speaking, miniature paintings were mainly part of manuscripts and illustrative in nature as they were meant to accompany a story or a text. My work at this point derives from miniature painting. I don’t think my practice can be put into that box anymore. It’s almost unfair to both. Over the years I have focused in developing a critically-charged approach towards this genre while continuing to explore the possibilities of it. I carry on experimenting with the formal build of Indo-Persian paintings with an interdisciplinary approach such as painting, drawing, photography, video, sound, installations, and collaborations with other artists.

S.: You seem to have a kind of panoramic and expansive approach to what you explore in your work. War Rugs with Love (2013) seems decidedly political in the sense that you address topics of war and peace/conflict and resolution. Black Sheep’s Wool (2012) was seemingly based on the similarities and differences “of skin, race, language and appearance.” At the other end of the spectrum, the pieces that you sent me, such as the “I Am a Tree” series, seem to be meditations on nature. Taken as a whole, I really see a sense of optimism and, even with the overtly-political works, a kind of searching for solutions rather than broadcasting ideas of pure outrage. Do you agree with this? If so, how do you tune your perspective in looking for hope or resolutions in the contemporary world, which can at times seem completely hopeless?

N.B.: I work with variety of themes, possibly because I make worked in many different places, and places inspire me, people inspire me, cultural and political boundaries intrigue me. They provide a space for discussion and investigation in my precise. I usually don’t stick to one theme I don’t think it’s really possible in my case. I don’t settle very easily.

Well now that I think of it, I sent you very few images that are not giving you a clear picture of the work. “I Am a Tree” has text pieces along with it. It is a series of nine paintings of trees and eight text sheets. The text is an excerpt from Orhan Pamuk’s novel “My Name is Red,” in which a drawing of a tree questions its existence as it doesn’t know which story it belongs to. The drawing never got into a book and is feeling lost and asking the viewers to not take it as a tree but take it for what it means. There is a video piece in the show too: Keep this Game out of Reach of Adults. It can also be seen on my website.

S.: In this same regard, much of your work at first glance seems colorful, if not playful, and naturally inviting to the audience. Do you feel as if you use this approach as a way to disarm the viewer to engage them into deeper and more cerebral concepts?N.B.: I don’t really stick to a palate, too. There was a time I didn’t touch a color other than Payne’s Gray for over three years. Even in this show, one work is entirely monotone while the other has a pop of color and then there is a bigger painting which has crazy colors. Colors don’t dictate my ideas; it’s the other way around … mostly. What I like about colors is that they can be very deceptive. Bright colors can say “Happy” when the work says “Irony”; you know what I mean.

![[A detail shot from Nida Bangash's series, "I Am a Tree," gouache and ink on waslee paper; 4" X 6"; 2013.]](https://starehouse.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/01-nidabangash-i-am-a-tree-01-gouache-and-ink-on-waslee-paper-4x-6-inches-2013-4.jpg?w=960)

[A detail shot from Nida Bangash’s series, “I Am a Tree,” gouache and ink on waslee paper; 4″ X 6″; 2013.]

I am a tree and I am quite lonely… They allege that I’ve been hastily sketched onto nonsized, rough paper so the picture of a tree might hang behind the master story teller. True enough. At this moment, there are no other slender trees beside me, no seven-leaf steppe plants, no dark billowing rock formations which at times resemble Satan or a man and no coiling Chinese clouds. Just the ground, the sky, myself and the horizon. But my story is much more complicated.

The essential reason of my loneliness is that I don’t even know where I belong. I was supposed to be part of a story, but I fell from there like a leaf in autumn.

… I know nothing about the page I’ve fallen from. My request is that you look at me and ask: “Were you perhaps meant to provide shade to Mejnun disguised as a shepherd as he visited Leyla in her tent?” or “Were you meant to fade into the night, representing the darkness in the soul of a wretched and hopeless man?” How I would have wanted to complement the happiness of two lovers who fled from the whole world, traversing oceans to find solace on an island rich with birds and fruit! I would’ve wanted to shade Alexander during the final moments of his life on his campaign to conquer Hindustan as he died from persistent nosebleed brought on by sunstroke. Or was I meant to symbolize the strength and wisdom of a father offering advice on love and life to his son? AH, to which story was I meant to add meaning and grace?

I don’t want to be a tree; I want to be its meaning.”

(An excerpt from Orhan Pamuk’s 1998 novel “My Name is Red,” which inspired Nida Bangash’s series, “I Am a Tree.”)

Daniel A. Brown

starehouse@gmail.com

![[Installation shot of Nida Bangesh's work at Clay and Canvas Studios.]](https://starehouse.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/img_2513.jpg?w=975&h=400)